login/create account

login/create account

are simple finite graphs, then

are simple finite graphs, then  .

. Here  is the tensor product (also called the direct or categorical product) of

is the tensor product (also called the direct or categorical product) of  and

and  .

.

This beautiful and seemingly innocent conjecture asserts a deep and important property of graph coloring. It is undoubtedly one of the most significant unsolved problems in graph coloring and graph homomorphisms.

We write  if there is a homomorphism from

if there is a homomorphism from  to

to  . The graph

. The graph  has a two natural projection maps (projecting onto either the first or second coordinate), and these maps are homomorphisms to

has a two natural projection maps (projecting onto either the first or second coordinate), and these maps are homomorphisms to  and to

and to  . So, in short,

. So, in short,  and

and  . A graph is

. A graph is  -colorable if and only if it has a homomorphism to

-colorable if and only if it has a homomorphism to  . Combining this with the transitivity of

. Combining this with the transitivity of  we find that

we find that  (indeed, if

(indeed, if  , then

, then  and

and  , so

, so  - equivalently,

- equivalently,  is

is  -colorable). So, the hard direction of Hedetniemi's Conjecture is to prove that

-colorable). So, the hard direction of Hedetniemi's Conjecture is to prove that  .

.

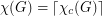

Let's define  to be the proposition that

to be the proposition that  whenever

whenever  and

and  . Then the above conjecture is equivalent to the statement that

. Then the above conjecture is equivalent to the statement that  holds for every positive integer

holds for every positive integer  . Now

. Now  holds trivially and

holds trivially and  follows from the observation that the product of two graphs each of which contains an edge is a graph which contains an edge. The next case is quite easy too, if

follows from the observation that the product of two graphs each of which contains an edge is a graph which contains an edge. The next case is quite easy too, if  and

and  , then both

, then both  and

and  contain an odd cycle. Since the product of two odd cycles contains an odd cycle, this shows

contain an odd cycle. Since the product of two odd cycles contains an odd cycle, this shows  . The next case up,

. The next case up,  was proved by El-Zahar and Sauer by way of a beautiful argument. It is open for all higher values.

was proved by El-Zahar and Sauer by way of a beautiful argument. It is open for all higher values.

A key tool in the proof of El-Zahar and Sauer is the use of exponential graphs. For any pair of graphs  the exponential graph

the exponential graph  is a graph whose vertex set consists of all mappings

is a graph whose vertex set consists of all mappings  . Two vertices

. Two vertices  are adjacent if

are adjacent if  is an edge of

is an edge of  whenever

whenever  is an edge of

is an edge of  . It is easy to see the relevance of

. It is easy to see the relevance of  to this problem. If we have an

to this problem. If we have an  -coloring

-coloring  of

of  , then for every vertex

, then for every vertex  , there is a mapping

, there is a mapping  given by

given by  . This associates each

. This associates each  with a vertex in

with a vertex in  . Now it is easy to verify that whenever

. Now it is easy to verify that whenever  are adjacent vertices in

are adjacent vertices in  , the maps

, the maps  and

and  are adjacent in

are adjacent in  . Rather more surprisingly, Hedetniemi's conjecture may be reformulated as follows:

. Rather more surprisingly, Hedetniemi's conjecture may be reformulated as follows:

, then

, then  is

is  -colorable.

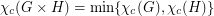

-colorable. The following conjecture asserts that Hedetniemi's conjecture still holds with circular chromatic number instead of the usual chromatic number. Here  is the circular chromatic number of

is the circular chromatic number of  . Since

. Since  this is a generalization of the original conjecture.

this is a generalization of the original conjecture.

and

and  are finite simple graphs then

are finite simple graphs then  .

. A graph  has circular chromatic number

has circular chromatic number  for positive integers

for positive integers  if and only if

if and only if  has a homomorphism to the graph

has a homomorphism to the graph  . This is a graph whose vertex set consists of

. This is a graph whose vertex set consists of  vertices cyclically ordered, with two vertices adjacent if they are distance

vertices cyclically ordered, with two vertices adjacent if they are distance  apart in the cyclic ordering. So again, we may state this conjecture in terms of homomorphisms to graphs of the form

apart in the cyclic ordering. So again, we may state this conjecture in terms of homomorphisms to graphs of the form  . More generally, let us call a graph

. More generally, let us call a graph  multiplicative if

multiplicative if  implies either

implies either  or

or  . Now Hedetniemi's conjecture asserts that every

. Now Hedetniemi's conjecture asserts that every  is multiplicative and Zhu's conjecture asserts that every

is multiplicative and Zhu's conjecture asserts that every  is multiplicative. With this terminology, El-Zahar and Sauer proved that

is multiplicative. With this terminology, El-Zahar and Sauer proved that  is multiplicative. A clever generalization of their argument due to Haggkvist, Hell, Miller and Neumann Lara showed that every odd cycle is multiplicative. Recently, Tardif bootstrapped this theorem with the help of a couple of interesting operators on the category of graphs to prove the

is multiplicative. A clever generalization of their argument due to Haggkvist, Hell, Miller and Neumann Lara showed that every odd cycle is multiplicative. Recently, Tardif bootstrapped this theorem with the help of a couple of interesting operators on the category of graphs to prove the  is multiplicative whenever

is multiplicative whenever  . Ignoring trivial cases and equivalences, these are essentially the only graphs known to be multiplicative.

. Ignoring trivial cases and equivalences, these are essentially the only graphs known to be multiplicative.

It might be tempting to hope that all graphs are multiplicative, but this is false. To construct a non-multiplicative graph, take two graphs  with the property that

with the property that  and

and  (for instance

(for instance  and the Grotzsch Graph). Now

and the Grotzsch Graph). Now  is not multiplicative since

is not multiplicative since  and

and  , but

, but  . It seems that there is no general conjecture as to what graphs are multiplicative. Some other Cayley graphs look like reasonable candidates to me (M. DeVos), but I haven't any evidence one way or the other.

. It seems that there is no general conjecture as to what graphs are multiplicative. Some other Cayley graphs look like reasonable candidates to me (M. DeVos), but I haven't any evidence one way or the other.

Poljak and Rodl defined the function  . So, Hedetniemi's conjecture is equivalent to

. So, Hedetniemi's conjecture is equivalent to  . Using an interesing inequality relating the chromatic number of a digraph

. Using an interesing inequality relating the chromatic number of a digraph  to the chromatic number of a type of line graph of

to the chromatic number of a type of line graph of  , they were able to prove the following quite surprising result: Either

, they were able to prove the following quite surprising result: Either  is bounded by

is bounded by  or

or  .

.

There are a number of interesting partial results not mentioned here, and the reader is encouraged to see the survey article by Zhu.

Drupal

Drupal CSI of Charles University

CSI of Charles University